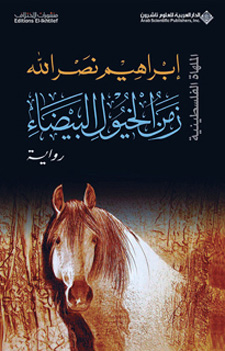

The Time of White Threads: The story of a village that summarizes the history of an entire people

Book Summary

The Time of the White Horses tells how a place turns from a home to a memory that resists forgetting, and how storytelling becomes an act of survival.

About This Book

Ibrahim Nasrallah's The Time of White Horses is a long narrative epic that opens a window on a village called al-Hadiya on the outskirts of Jerusalem, and accompanies it through major transformations: Late Ottoman rule, the British Mandate, and the approach of 1948. The narrative walks with us through three generations of one family: Mahmoud (the village elder), his son Khaled, and his grandson Naji. In the hands of all of them stand the horses, especially the white mare Hamama and her offspring, not as a novelistic decoration, but as a living symbol of memory, dignity, and the land that does not want to forget its name.

At the beginning of the novel, Hadiya enters like a whole world: Harvest, wedding, reconciliation, storytelling evenings, and customs that protect people from fragmentation. Mahmoud here is not a showy hero, but a man who knows that the village's strength is in its cohesion: He extinguishes disputes before they turn into revolts, balances justice and prestige, and tries to keep life as "normal" as possible despite the shadow of the distant state, the weight of levies and conscription, and the fear of a changing time. The village seems to be planting, knowing that the wind may come, but planting so as not to believe that the wind is the end.

As the narrative center shifts to Khaled, the friction with history becomes more direct and harsher. Khaled inherits his father's sense of protecting the community, but the tools that confront him grow: A new authority, new laws, an administrative language that doesn't resemble the language of the people. It is here that Dove, the white mare, shines as the symbolic heart of the novel: Khaled sees her not as "property" but as "trust" and treats her as a road companion and a witness to a narrowing time. Its whiteness on the plain is not just beauty; it is a sign that the soul can still run, that the earth still remembers the feet of its owners. When their offspring are born later, it is as if the memory itself is reproduced: From body to body, from generation to generation.

The British Mandate enters Hadiya through details that seem administrative on the surface but drag behind them entire destinies: A police station, traffic permits, land records, courts that do not understand people's dialect and do not recognize their customs, and maps that rename things. The villagers are gradually discovering that the law is not as impartial as it is said to be, and that the land whose boundaries were once defined by stone, tree and watering hole is now measured by ink and stamp. In the background, the pressure of settlements, migrations and confrontations escalates, and the roads turn into questions: Who passes, who prevents, who decides that this field is yours or not? The novel does not say this as a history lesson, but as a daily pulse: A mother waits for her son when he is late, a man reviews his papers as if reviewing his life, and a village that feels that the air itself is being monitored.

In the midst of all this, the author does not paint the village as angels. On the contrary, what makes the novel more interesting is that it exposes internal cracks as well: Greed, envy, small deals that open a big door, and betrayals that don't always start out as betrayals, but as "forced" concessions that turn into habits. Some minor characters appear, disappear, and return with a different face, and the novel tells you frankly: Chaos does not only create victims, but also those who profit from the destruction of others. On the other hand, there are heart-warming moments of solidarity: Bread is shared, men take turns guarding, women carry the burden silently and make patience a real strength.

As time passes, the siege intensifies until it reaches forms of siege and direct pressure on Hadiya. At this point, Khaled has to think about protecting the people, not with weapons alone, but with subterfuge and managing fear so that it does not turn into chaos. It is at this point that the white horses take on their harshest meaning: The preservation of horses is not a luxury or folklore, but a defense of a part of the soul. When a stranger steals something from the village, he is not just stealing goods, he is stealing a symbol of dignity. When a pigeon or one of its descendants survives, the reader feels that something of meaning has survived with it.

Then comes Naji, Khaled's grandson, as the son of a generation that was born hearing the story about itself before living it. Naji inherits the worries of the elders before he inherits their dreams, and grows up with a heavy question: How can you have a house and land, and then come a time when you have to explain to a child why the road is dangerous, why the night is heavier than before? As 1948 approaches, the signs accelerate: Bad news about other villages, roads closing, and old certainties eroding day by day. The novel does not follow a single "event" so much as a condition: How human beings change when survival itself becomes a daily decision.

The beauty of The Time of White Horses is that it blends the epic with intimate details: You'll find scenes close to cinema (decision-making councils, guarded nights, tension that builds and then subsides), but you'll also find a subtle charm in seemingly simple things: The smell of the dirt after the rain, the feel of the bridle, the look of the horse before the gallop, the trembling of the hand holding the door of the house when an unknown assailant comes. It is these details that make the ending both painful and illuminating: Painful because you have lived with Hadiya as if it were your home, and illuminating because the novel says that memory, when turned into a story, becomes a form of survival.