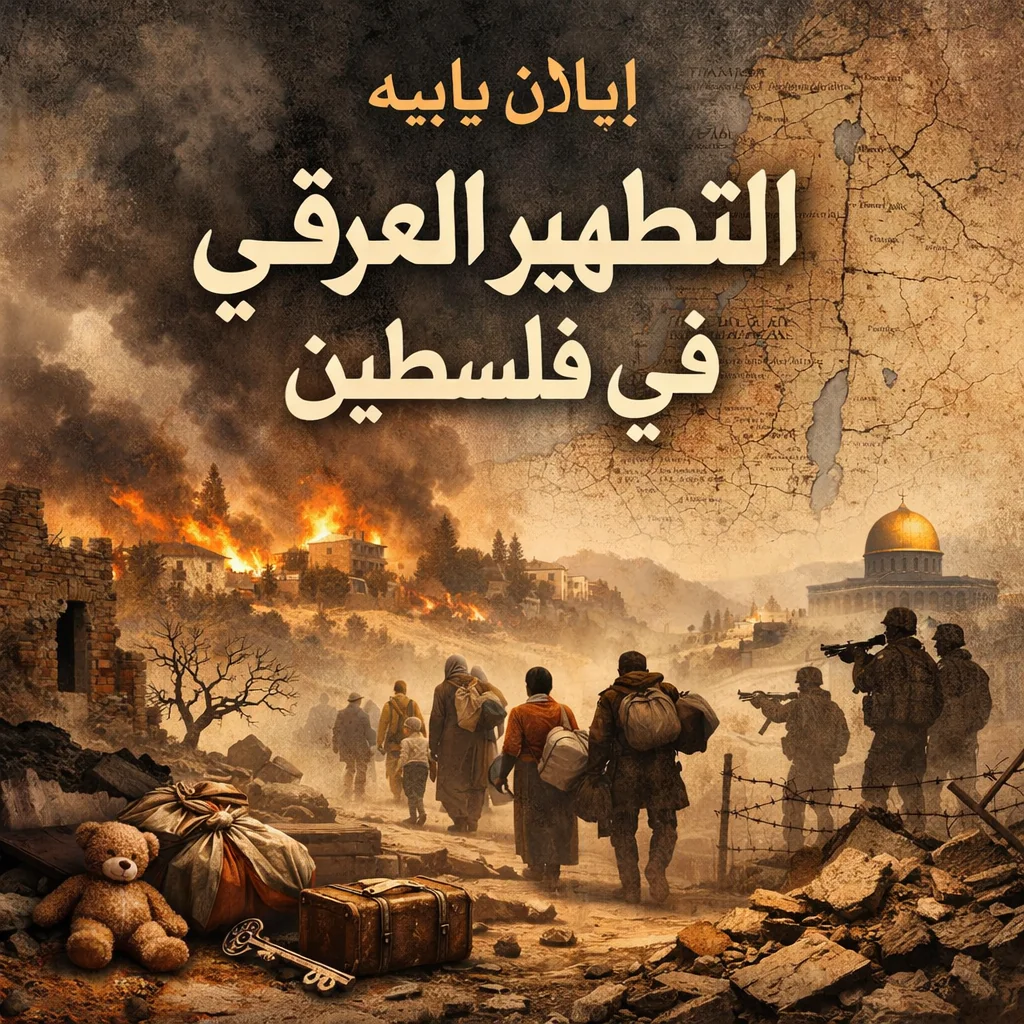

Ilan Pappé takes you behind the scenes where decisions were made and proposes a shocking reading of what happened in 1948: it was not a random displacement imposed by chaos, but a pre-determined depopulation policy. Through documents, maps, and military plans, Pappé paints a picture of a project to empty the land of its original inhabitants to reshape the demographic reality.The strength of the book is not in the details alone, but in its daring to change the angle of view: when we change the name of what happened, we change the questions of ethics, responsibility, and the future.Ethnic Cleansing is not a traditional history book, but an invitation to understand how a political decision can create a long memory and a never-ending struggle.

Imagine entering a cold archive room, opening an old file drawer, and finding something like a "secret map" of an entire country: pages about villages, roads, water springs, hills, family names, and little notes about "who lives here" and "how to get in".It is from this opening image that Ilan Pappé's book Ethnic Cleansing begins: not only as a tale of war, but of a long "preparation" that culminated in a decisive moment that changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and established a conflict that has yet to end.

Pappé's central idea is clear and sharp: what happened in 1948 cannot be understood only as a by-product of the war, but as a systematic policy aimed at removing as much of the Arab population from as much of the land as possible.He is not content with describing "displacement" or "refugees"; he insists on using a specific analytical lens: replacing the "war model" with the "ethnic cleansing model" in reading 1948, because this substitution changes the nature of the ethical and political question: are we facing the chaos of war, or a demographic displacement project with a logic and tools?

How does Pappé build this claim? He relies on two parallel tracks: the planning track and the implementation track. In the planning track, he highlights an early intelligence project called "Village Files" in the years 1940-1947: collecting detailed information about Arab villages, maps, data, and social profiles.He then links this to a series of military plans that culminated in Plan Dalet, which Pappe sees as an inflection point: its logic is not only "defense" but the creation of a new demographic reality by controlling and emptying areas.

The process of implementation is presented as a chronological narrative: decisions, operations, waves of displacement, villages abandoned by their people under the pressure of fear, expulsion or the collapse of protection, and then a new reality imposed afterwards. Pappé describes the "decision kitchen" through a group he calls "The Consultancy": a narrow circle of people who met or consulted on how to manage the phase, and presents it as the organizing mind of the policy he calls ethnic cleansing.Academic reviews of the book point out that Pappé presents this group and the Dalet Plan as an essential part of his argument, and considers them "strong evidence" of intent and policy, rather than a mere coincidence of war.

Pappé opens an important comparative window here: he does not treat "ethnic cleansing" as a slogan, but rather as a concept with a systematic definition in the international law literature, associated with a policy aimed at eliminating a group from a given territory on the basis of national, religious or ethnic identity, often through violence or the threat of violence, usually in the context of military operations.To emphasize the concept, Pappé sometimes compares it to what happened in Bosnia in the 1990s: not to say that the two histories are identical, but to say that the "language of description" should be the same as the action: organized depopulation, not spontaneous migration.

But the book is not just "arguments and documents." Its narrative strength is that it insists on the question of memory: "How can an event of this magnitude be erased from the public conscience?" Here the book becomes more like a story of a dispute over narratives: one that says "they left because the war broke out" and one that says "they were pushed to leave as part of a policy.Pappé argues that not adopting an "ethnic cleansing lens" has historically helped to perpetuate denial or mitigate responsibility, because war always provides an excuse: "That's how wars are." Calling the act by its name opens a different door: recognition, accountability, and the search for transitional justice or a moral and political settlement.

The Encyclopedia Britannica summarizes that the 1948 war is remembered by Palestinians as the "Nakba" because of the massive displacement that resulted, and by Israelis as the "War of Independence," which means that the same event lives in two conflicting memories.

Pappé belongs to a stream of "new historians" who have reread state archives and debated the responsibilities and consequences of the war, but his advantage is that he pushes the conclusion to its moral extreme: not just harsh consequences, but a policy of displacement that should be recognized as a historical crime.

However, the book's most profound question is not only "What happened?" but "What does it mean to recognize what happened?" Pappé concludes with the implicit message that the future of any settlement cannot go beyond 1948 as a closed event because it has become an ongoing structure in people's lives: refugees, memory, denial, and the struggle for legitimacy.He writes as if he is sending a message to two audiences: to those who lived the experience and want a language that recognizes it, and to those who fear recognition because it threatens a founding myth. He bets that recognition, however difficult, may be the only way to imagine a "shared future" that is not based on denial of the past.

Comments