Sleep is no longer seen as a personal behavior associated with comfort or a luxury that can be dispensed with, but has become one of the most sensitive biological indicators of brain health. In the last two decades, sleep has moved from a "daily habit" to a central position in neuropreventive medicine, as research has shown that changes in sleep duration, quality and regularity may predate cognitive decline and dementia by many years. In this sense, sleep is no longer just a consequence of health status, but has become an early warning tool that reveals a neurological pathway whose symptoms may not appear until later in life.

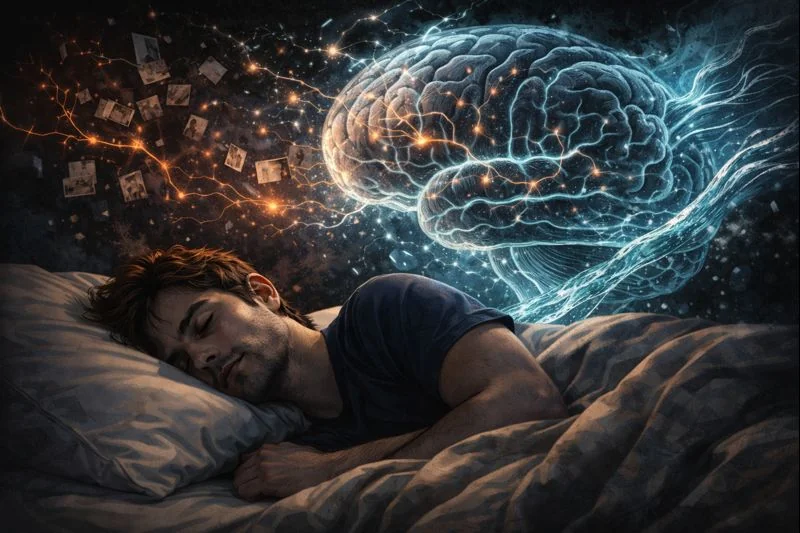

Scientifically, the brain does not go dormant during sleep, but rather begins one of its most active phases of internal maintenance. In deep sleep, the glymphatic system is activated, a neuro-cleaning network responsible for removing metabolic waste products accumulated between neurons during waking hours. These waste products include dangerous proteins such as beta-amyloid and tau, the accumulation of which is directly linked to dementia and Alzheimer's disease. During sleep, neurons temporarily shrink, allowing the cerebrospinal fluid to flow more efficiently, as if the brain is undergoing a nightly cleaning process that cannot be performed while awake.

Experiments directly support this critical role of sleep. In a pivotal experiment in mice, sleep has been shown to widen the space between neurons by more than 60% compared to the waking state, increasing the efficiency of exchange between CSF and interstitial fluid and accelerating the removal of waste products. In humans, accelerated neuroimaging studies have observed that NREM deep sleep waves are accompanied by hemodynamic oscillations followed by a regular flow of cerebrospinal fluid, in a delicate harmony between the brain's electrical activity and fluid movement within it, favoring neural maintenance and long-term cleaning.

But why has sleep become an early medical indicator of dementia risk? Because disruption of sleep is not limited to fatigue or poor concentration, but is statistically associated with long-term cognitive outcomes. In a long follow-up of nearly 25 years in the Whitehall II study, shorter sleep, six hours or less, in middle age was associated with a significantly increased risk of dementia compared to seven hours of sleep. At age fifty, the relative risk ratio was 1.22, rising to 1.37 at age sixty. Maintaining a short sleep pattern across the lifespan was associated with a nearly 30% increase in dementia risk, even after adjusting for behavioral, cardio-metabolic, and mental health factors.

In a parallel trend, observational studies show that prolonged sleep in old age may not necessarily be a sign of health, and may even be associated with a higher risk of dementia. A multicenter study found that sleeping more than nine hours in late life was associated with a significant increase in the risk of dementia, supporting the hypothesis that sleep changes may sometimes be an early sign of an underlying disease process, rather than a direct cause. Sleep disturbances are no longer interpreted as a consequence of aging, but rather as warning signs for brain health.

This shift in understanding has led major research organizations, such as the National Institutes of Health, to invest in studies that use sleep data, in terms of duration, depth, and regularity, as predictive tools for early detection of cognitive decline. Ultimately, sleep reveals itself as a very honest biomarker, reflecting the brain's ability to repair and clean up over time. A brain that is consistently deprived of adequate and deep sleep does not pay the price immediately, but rather stores the effects of this deprivation in its neural architecture, to manifest later in the form of deteriorating memory and cognitive function. Sleep hygiene is not a luxury, but an essential preventative strategy to protect the brain before it's too late.

Comments