I. Introduction

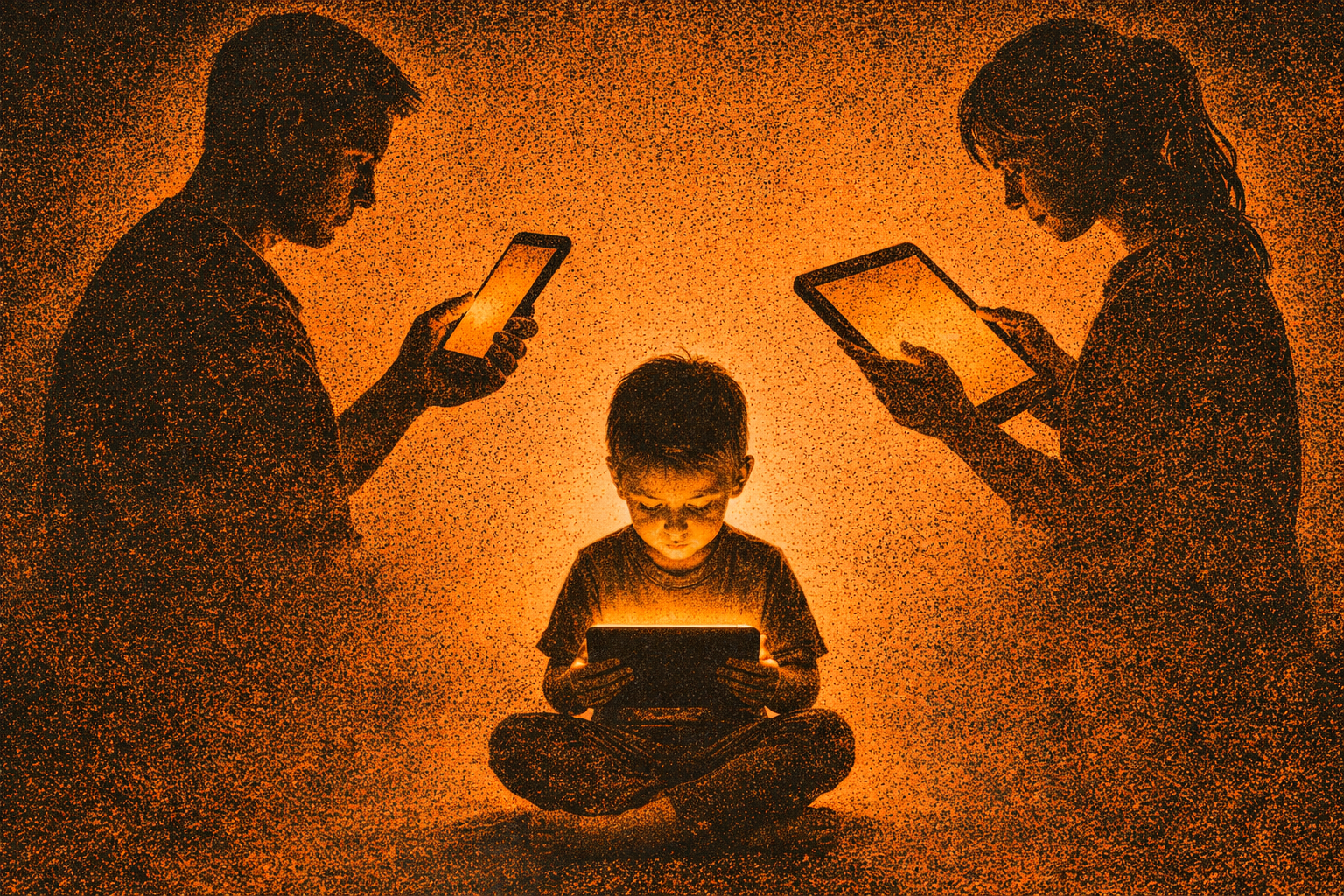

Screens have become a structural part of today's childhood, not as a fleeting entertainment device but as a daily living environment. Studies show that 40% of children own a tablet by the age of two, and nearly one in four children own a personal phone by the age of eight, while the average screen time for ages 0-8 remains around 2. 5 hours per day (Common Sense Media, 2015).(Common Sense Media, 2025). This overwhelming prevalence means that children are not only watching, but learning to attend to the world through a digital medium that accompanies them during meals, waiting, and trips, and crowds out central developmental activities such as reading, playing, and talking.The same report also shows that the daily reading habit among ages 5-8 has declined from 64% to 52% since 2017, in parallel with the relative stability of screen time, suggesting that the issue is not an increase in time alone but shifts in priority and routine (Common Sense Media, 2025). Although public health recommendations for early childhood emphasize reducing sedentary behavior in front of the screen, the reality indicates that the screen has sometimes become a calming solution or a temporary sitter under work pressure and time constraints (World Health Organization, 2019).

Therefore, the paper poses its central question: Who raises children in the digital age? Education is no longer limited to the family and school, because content no longer passes as a simple open/close choice, but passes through the algorithm as an invisible actor that rearranges what the child sees moment by moment.The algorithm here is a recommendation system that captures the signals of interaction (duration of viewing, repetition, clicking, stopping) and then builds a suggested path that increases the likelihood of continuation, so that what appears next becomes part of an ongoing process of socialization that the adult is not always aware of (Radesky et al., 2024).Accordingly, the paper asks: Who determines what children are exposed to? How does this affect their cognitive and psychological development, especially language, imagination and concentration? What values are unconsciously transmitted through digital role models and popular content?

Second: The educational shift from the family to the algorithm

Screens today act as an unspoken educational actor that is not accountable in the sense that we hold schools, families, or even traditional television content accountable. Whereas parents previously controlled the "gateway" of content entering the home, modern platforms are based on an endless flow and a personalized recommendation that changes moment by moment.In this context, parenting is no longer a matter of "choosing a program" or "blocking a channel," but a confrontation with a recommendation system built on an attention economy: what gets the longest stay and what gets the most scrolling is what gets prioritized.

Within this shift, algorithms work to guide what the child sees without the family's awareness through three overlapping mechanisms: first, "ranking" which makes certain topics more present, even if the child does not directly search for them. Second, "repetition" which creates learning by continuous exposure, so that images, behaviors, and vocabulary become a daily habit.Third, "reward" through notifications, likes, and smooth transitions, which creates a simple conditional pattern: pay more attention to get more fun. Here, the difference between "use" and "upbringing" appears: use means a tool within a schedule and a goal, while digital upbringing means that the platform has become a parallel parenting environment, creating habits of attention and adjusting the standard of value and acceptance.

The concept of educational authority changes accordingly: from command and guidance to attraction and digital reward. The child does not only "disobey" the parents; he finds a very tempting alternative that offers him instant pleasure and constant presence, and redefines "boredom" as an issue that must be eliminated immediately. Over time, the algorithm becomes a party that determines the child's daily rhythm: stealing sleep through night scrolling, reshaping play time by turning it into watching, and pressuring attention by cutting it into short units.On the other hand, the role of direct supervision is diminishing in the face of false confidence in the platforms: some parents assume that "children's content" is automatically safe, or that a large platform means effective guarding, while the reality is that so-called "children's content" may still be guided by an algorithm that maximizes survival time, not quality of education.

Families today face real-life pressures: work shifts, daily congestion, and multiple responsibilities make "screen delegation" a practical and quick solution, especially in homes that lack free and safe alternatives to play and learn. Here the family appears between forced delegation and educational impotence: not because parents do not want to educate, but because the digital environment has imposed its conditions and competes with the family for the child's attention in the language of instant pleasure.

The analytical answer is not "when the child watches too much" only, but when the family loses its ability to contextualize and make sense of what the child sees, and when the flow of content becomes the one that shapes daily habits and redefines what is normal, acceptable, and interesting. Then the screen is no longer a tool in the hands of education, but education itself becomes part of a recommendation system, writing a "daily biography" of clips, standards, and emotions for the child.

Third: Reshaping the child from within: language, imagination, and focus

One of the most important issues here is language: early childhood is shaped by live verbal interaction, where the child learns vocabulary, context, tone, and reciprocity. Recent studies that used longitudinal measurement of elements of parent-child talk (adult word count, child expressions, and dialogic exchange) found a negative correlation between increasing screen time and indicators of crosstalk at 12 to 36 months of age; in plain language: the more screen time, the fewer opportunities for crosstalk that builds both language and attachment (Brushe et al., 2024).A child who spends more time in front of fast content may hear a lot, but he does not participate as much, nor does he practice building a sentence, negotiating meaning or understanding an immediate social context. Hence the shift from complex expression to gestures, abbreviations and quick responses, not only in adolescents, but as a general climate that presses for speed and brevity even before language tools are fully developed.

Imagination is another arena that is affected. Free interactive imagination is fed by space and symbolic play: a box becomes a ship, a spoon becomes a microphone, a short story becomes a whole world. But when the screen becomes the main source of wonder, imagination turns into canned imagination: ready-made images, quick plots, and emotion-driven effects, and the child's ability to create his own world diminishes.Over time, symbolic play recedes in favor of continuous viewing, and boredom - once the fuel for innovation - becomes unbearable. This shift is also reflected in the relationship with learning: learning by watching is different from learning by trial and error. A child who learns through actual play experiences the resistance of matter, the limits of time, and the sequence of cause and effect, while a child who learns through a quick clip may get a result without a path, a solution without attempts, and pleasure without patience.

Short-form content platforms, due to their fast-paced sequencing, do not train the child in deep attention so much as in immediate response: quick transition, quick reward, new topic before comprehension is complete. Recent research literature links heavy use of short-form video media to greater indicators of attention issues, and the findings are considered preliminary evidence of a link worthy of scientific attention, especially when use is combined with addictive behavior or prolonged exposure (Chiencharoenthanakij et al., 2025).(Yamamoto et al., 2023). On the other hand, this does not mean that every screen is automatically harmful; it does mean that when screen time becomes a substitute for interaction, play, and sleep, it becomes a stressor on the development of attention and self-regulation (Yamamoto et al., 2023).

The knowledge that used to require time (reading, questioning, trying) becomes fragmented knowledge: short information, self-contained images, visual saturation without depth. The criterion of value shifts from understanding to excitement and from answering to spreading. With this context, the concluding question becomes: What kind of mind are we creating through the screen? A mind accustomed to speed and impatience? Or a mind that we can protect through conscious management that makes the screen a means within a context, not a context that replaces life?

The analytical answer here is that the mind that is formed is not the result of an abstract screen, but rather the result of a system of use: when the screen is at the center of the day without clear boundaries, when short content becomes the main cognitive food, and when the accompanying dialogue is absent, then the structure of attention, language and imagination gradually changes. But when screens are part of a conscious family plan, under supervision and interaction, and in parallel with play, movement and adequate sleep, technology may turn from a force of dismantling to a learning tool, but this transition requires a basic condition: that the family returns to the site of meaning making, not just temporal control.

Fourth: Values and Role Models: Silent Screen Education

Values are not transmitted only through a sermon or a moral lesson, but through what is repeated, what is rewarded, and what becomes "normal" in the eyes of the child. Here lies the danger of education with screens: it raises silently through digital role models. While role models were historically distributed among parents, teachers, and the local environment, today the role model is often an "influencer" about whom the child only knows what the video shows: a polished body, a chosen life, quick success, and apparent profit.In this context, the prevailing values in popular content become pedagogical drivers: fame as the standard of value, showmanship as the language of acceptance, profit as the proof of success, and formal excellence as the shortcut to life. In turn, important moral contexts are absent: the meaning of gradual effort, the value of error and learning, the idea of privacy, and respect for boundaries.

All of this is amplified because the environment itself is based on rewarding reactivity, not depth. Content that provokes anger, laughter, or shock goes viral and becomes an informal "school" for emotion.Recent health warnings indicate that we are facing an environment that is not yet fully equipped to ensure its safety for young people, and that its risks are not marginal, but require measures to minimize harm, which is reflected in the value dimension: when a platform is designed to maximize interaction, it will give priority to what appeals to emotion, even if it is superficial or misleading (U. S. Surgeon General, 2013).Surgeon General, 2023). The issue of early comparison also arises here: the child or adolescent measures himself by likes and engagement, and develops a conditional relationship with himself: I am "good" when I receive interaction, and I am "less valuable" when he is absent. Over time, self-confidence becomes hostage to a fickle public mood, and social acceptance becomes a number.

The gap between home and screen values emerges as a crisis of education rather than technology. The home may teach the value of humility, while the screen rewards showmanship; the home may teach patience, while the screen rewards speed; the home may present human models with their weaknesses and fatigue, while the screen presents "fabricated" models without context.When parents do not accompany what the child watches with a discussion that contextualizes it, and when there is no common language between two generations about what is "real" and what is "theatrical", value education gradually becomes hollow, and the child becomes a recipient of unspoken rules: do what brings interaction, show what arouses attention, and avoid what slows down the spread. This is a silent but effective form of education.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Conscious Pedagogical Role

The paper comes to the conclusion that the question "Who actually raises children?" is no longer a rhetorical question; in many environments, algorithms participate with the family and school in shaping the child by controlling attention, determining what is repeated, and creating role models. However, the issue is not the screen as a tool, but the delegation of education to it without context, without dialogic accompaniment, and without balance with sleep, play, and live interaction.What is needed is a digital educational awareness that is not based on abstract prohibition, but on partnership: a clear family plan, accompanying the child in its content, promoting realistic alternatives for fun and meaning, and restoring the role of the family as a value reference and not just a temporal monitor. At the general level, the need remains for educational and awareness policies that take into account that technology should serve the interest of the child before commercial considerations (UNESCO, 2023), while opening a new research horizon on education in the age of artificial intelligence and more complex algorithms.

Comments