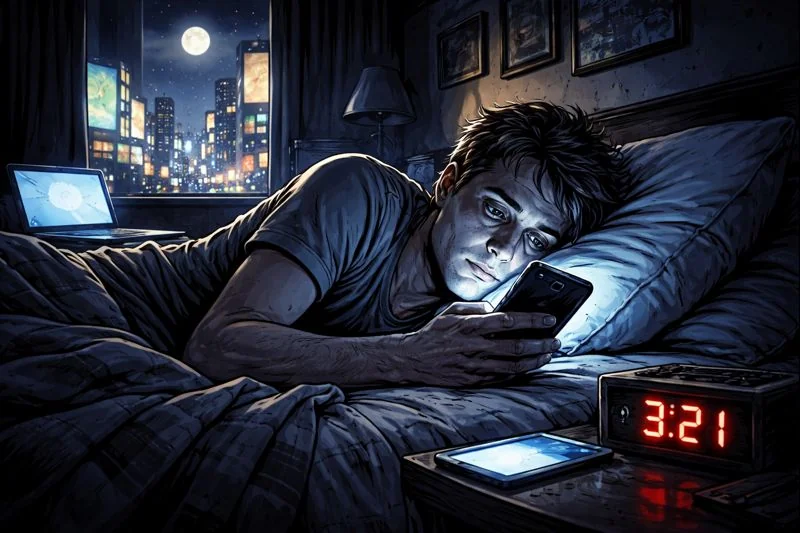

Insomnia in the age of screens is no longer just "bad habits" before bed, but a daily glitch in the way the brain understands the sign of night itself. Historically, the body picked up on simple and constant cues: Lights go down, sounds go quiet, social activity dies down, and the "night system" automatically kicks in: Vigilance decreases, melatonin rises, and the neural circuits that consume attention slow down. Today, night doesn't come so easily; we carry a "little sun" in our pocket that not only lights up, but calls out, surprises, rewards, and demands a response. This is where the modern idea of insomnia begins: A circadian confusion between light, content, and constant stimulation.

Light is the gateway to the story, but it's not the whole story. Screens, especially in the evening hours, present light spectrums (especially blue) that convince the brain that the day is not yet over. This delays the "start of night" announcement within the nervous system and shifts the timing of drowsiness. But even if we dim the brightness or use "night mode," a more subtle factor remains: Aroused attention. The brain doesn't measure the night by light alone, but also by the need to stay awake. When a person opens an interesting passage, engages in a discussion, or receives a sudden notification, the brain interprets it as a signal of danger or opportunity: "Stay tuned."

Notifications and quick content work on the logic of instant reward: Small doses of dopamine come at unpredictable intervals. This randomness makes the behavior more sticky, because the brain learns that the reward may come with the "next swipe". The phone turns from a tool into a mobile reward system that increases physiological arousal: A higher pulse, a seemingly gentle but genuinely alert tension, and a constant activation of attention networks. The trouble is that sleep requires the exact opposite: A gradual transition from concentration to a quiet fugue, from control to surrender. The brain can't ask for "sleep" while in digital hunting mode.

The confusion increases when mental work extends into the night: Writing, planning, responding, studying, or even organizing tomorrow's thoughts. It's not just the screen light that's the obstacle, it's the prefrontal cortex staying on: Problem-solving, decision-making, evaluating, comparing. This kind of activity creates a "cognitive residue" that lingers after the device is turned off: racing thoughts, reviews, and possibilities. The bed becomes an extension of the office, and the bedroom loses its function as a constant sign of rest.

The bottom line is that insomnia in the age of screens is a struggle between a biology designed to capture clear endings to the day, and a digital environment that eliminates endings. Night is no longer darkness, but a constant "modernization". When the brain doesn't know it's nighttime, it doesn't fight you, it believes the signals you give it: Light, content, and stimulation. Treating the issue starts with understanding it: It's not just about reducing light, it's about calming attention, and rebuilding rituals that clearly signal to the brain that the chase is over and sleep has begun.

Comments