Introduction

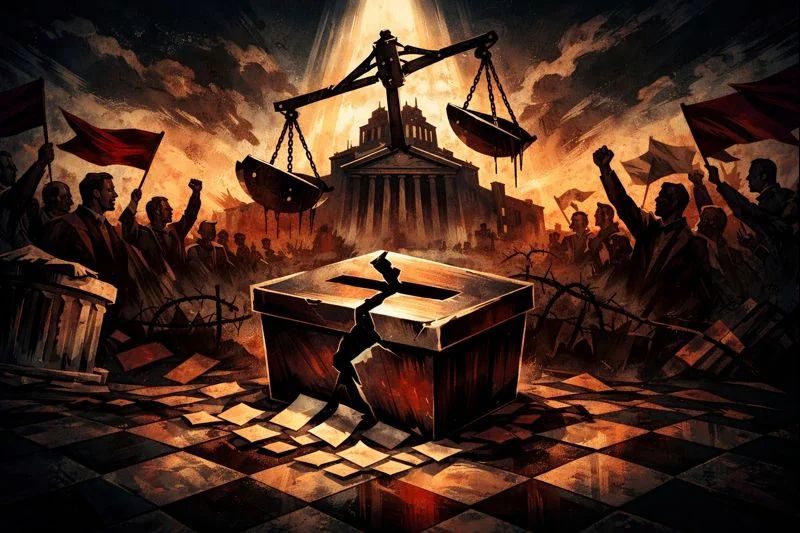

Imagine a society that wakes up every morning to the same news bulletin, but with diametrically opposite meanings: one group sees the government as a "savior" that protects stability and prevents collapse, and another group sees it as "illegitimate" whatever it does, and considers its decisions an extension of one group's dominance over another.In this scene, the dispute is no longer over taxation, education, or security policies, but over the other party's right to govern at all. This is where political polarization emerges as a condition that goes beyond the natural difference of opinion within democracies, because it redraws the symbolic boundaries of society: who belongs and who does not belong, who is considered patriotic and who is labeled a traitor, and who deserves to be heard and who should be excluded.

The danger of polarization is that it does not only change the results of elections, but changes the "acceptance criteria" itself, transforming political competition from a race of programs to a battle of mutual recognition. This paper starts from a central question: How does polarization change the sources of political legitimacy? Why does legitimacy move from being a product of performance, institutions and agreed-upon rules, to being an identity marker and a weapon in a hostile conflict?

First: Conceptual Framework: What is legitimacy and what is polarization?

Political legitimacy is the degree to which people accept the authority's right to govern, even when they do not agree with its decisions or reject some of its policies. The deep meaning of legitimacy is not to love the government, but to recognize that it represents a "general framework" that can be changed through rules and not by breaking them. Therefore, legitimacy is a condition for political stability, because it reduces the need for direct coercion and gives the state the ability to implement its decisions through voluntary compliance and relative trust.

First, there is legal/procedural legitimacy, which is based on elections, the constitution, the circulation of power, and the separation of powers, that is, on the idea that the road to governance passes through agreed-upon rules. Second, there is performative legitimacy, which stems from the ability of the authority to provide services, improve the economy, provide security, and reduce corruption, that is, a concrete achievement that justifies trust. Third, there is value/symbolic legitimacy, which is based on identity, religion, nationalism, and historical narrative, meaning the larger meanings that give people a sense of belonging, dignity, and recognition.

In contrast, political polarization does not simply mean the existence of multiple parties or ideological diversity, but rather the division of society into two or more camps so sharply that the political opponent becomes outside the circle of morality or patriotism in the eyes of his supporters. When the opponent becomes an "existential threat," it becomes difficult to accept the rules of the game, because any loss is a loss to the collective self rather than to a political party, and this is where the real erosion of the meaning of legitimacy begins.

Second: How does polarization damage legitimacy? Four main mechanisms

The first mechanism is the transformation of politics into identity. In a normal situation, citizens vote based on an interest, vision, or performance evaluation, even if this is tinged with emotion. But in severe polarization, voting becomes an expression of affiliation: I am with "my group" rather than with a specific program. Over time, the political identity hardens and overlaps with religion, nationalism, class, or region, so changing the political position becomes similar to changing the social affiliation, which is psychologically and symbolically costly.Legitimacy shifts from recognition of common institutions to loyalty to a particular group: what "my group" does is legitimate, and what "others" do is suspect, even if they abide by the law. With this shift, performance legitimacy also declines, because performance is no longer a sufficient criterion.The government may achieve economic growth, but the opposing camp interprets it as propaganda, "manipulation," or corruption, because its main conviction is not economic but identity-based. Thus, identity becomes a lens that precedes and reinterprets facts, and the state loses the ability to build inclusive legitimacy through achievement.

The second mechanism is the delegitimization of the opponent. When political discourse uses the vocabulary of treason and demonization, the opponent's electoral victory turns into a morally "unacceptable" result even if it is procedurally correct. Here, the political dispute is mixed with standards of political purity and impurity: whoever wins is not a competitor but a "danger." In this case, the elections themselves become an object of conflict rather than a means of resolving it, and questioning the results or the institutions organizing them becomes expected at every round.The most dangerous aspect of skepticism is that it generates a conviction among a wide audience that the rules are no longer neutral, and that they are merely a tool in the hands of the other party. The legal/procedural legitimacy then declines, because its essence is based on accepting the outcome of the game even when you don't like it. With repeated delegitimization, the room for "exceptional" behaviors expands under the pretext of "saving the country," so breaking the law becomes a moral justification for some actors, and politics turns into a battle for existence rather than a competition of programs.

The third mechanism is the politicization of institutions. In polarized societies, disputes do not remain only in parliament and parties, but extend to the judiciary, media, universities, oversight agencies, and public administration. Every institution that is supposed to serve as a common reference becomes in the eyes of part of society affiliated with a particular camp. When the judiciary or media lose their status as neutral arbiters, the state loses its symbolic tools in managing conflict.This leads to a vicious circle: the lack of trust in institutions leads each camp to seek its own tools (its own media, its own experts, its own narrative), which deepens polarization and increases pressure on institutions to identify with one of the two camps. In the end, the institution becomes a battleground rather than a common ground. In this sense, polarization not only weakens legitimacy, but turns it into a contested issue within each institution: who really represents the "state"? Who has the right to interpret the law? Who has the right to define the public interest?

The fourth mechanism is the economy of anger and digital media. Digital platforms do not act as a neutral medium; they are an environment that rewards interaction, and anger is often the fastest form of interaction to spread.When extremist messages are amplified, moderation becomes "cold" and unappealing, and a centrist voice that offers complexity or balance recedes. The result is a political marketplace based on constant provocation, where those who raise the temperature of identity and create a daily "enemy" or "scandal" win.With the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories, it becomes easy to undermine legal legitimacy by questioning elections, undermine performative legitimacy by portraying any achievement as a hoax, and undermine symbolic legitimacy by monopolizing patriotism. The public sphere turns into an arena of mobilization rather than debate, and the citizen becomes a consumer of ready-made identities rather than an actor discussing policies.

Third: How can legitimacy be restored in times of polarization? Analytical approaches

The first approach is to fortify institutions through transparent rules, effective oversight independence, and reducing the politicization of the judiciary and public administration. The point is not to "freeze politics," but to prevent turning the institution into a trophy. When citizens see that oversight works on everyone, and that punishment does not select opponents over allies, part of the trust will gradually return.

The second is managing diversity rather than suppressing it, by expanding spaces for negotiation and coalition, and electoral reforms that reduce the "all-or-nothing" game that makes every election a life-and-death battle. When politics becomes amenable to stable compromises, the tendency to delegitimize is reduced, because losing does not mean complete exclusion. The third is policies that alleviate the sense of exclusion: economic justice, fighting corruption, reducing opportunity gaps. Polarization feeds on groups feeling marginalized or denied recognition, even if this is not always accurate.

The fourth approach is to reform the digital sphere through platform transparency, fighting disinformation, supporting quality journalism, and developing media literacy skills. The goal is not strict censorship, which may increase paranoia, but to make the digital environment less conducive to radicalization and more conducive to trust.The fifth approach is to build an inclusive narrative, not in the sense of empty emotional rhetoric, but in the sense of a political identity that accommodates disagreement and redefines patriotism as an ability to coexist with difference, not a moral monopoly of one camp. Here, legitimacy returns to being a "contract" and not a "weapon": a contract that guarantees everyone's right to peaceful competition and prevents turning the opponent into a permanent enemy.

Conclusion

The crisis of political legitimacy in an era of polarization reveals that the issue is not only failed policies or weak governments, but the shifting meaning of legitimacy itself. When identity becomes the primary criterion, performative legitimacy declines as achievements are reinterpreted, legal legitimacy erodes as rules lose their neutrality in the eyes of the public, and symbolic legitimacy becomes an arena of monopoly and hostility.The most important lesson is that legitimacy does not collapse suddenly, but rather gradually erodes when the opponent becomes a permanent enemy, when institutions become a field of reckoning, and when digital media feed the economy of anger and reward extremism. This paper proposes a research direction that can be built upon: measuring polarization through indicators of trust in institutions and tracking the relationship between digital media consumption and the willingness to delegitimize opponents.

Comments